One mistake I’m beginning to get over, is thinking that proverbs I hear in the dojo are not general to Japanese culture, but are somehow specific to budo. Every time I’ve thought that, I’ve been wrong. Japan was run by a warrior class for hundreds of years. Needless to say, with that kind of history driving the culture, references to budo are quite common in everyday society. When things are very serious, it’s a “shinken shobu” 真剣勝負, a match with live swords.

There is a phrase often heard in budo circles that came up in a discussion recently. “Budo begins and ends with a bow.” The original Japanese is 礼に始まり礼に終わる (Rei ni hajimari rei ni owaru). omitting any reference to budo. This phrase is common in Japan, where everything begins and ends with a bow. It’s also where we non-Japanese trip over the translation.

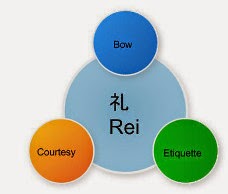

The “rei” 礼 in “Rei ni hajimari rei ni owaru.” is commonly translated as one of three things; bow, courtesy, or etiquette. Each of those is correct, and each of them is wrong. Each is correct in that it captures some component of rei. Each is mostly wrong because it misses the majority of the ideas, meanings and feelings embodied in the concept of rei.

Rei turns out to be a much larger concept than any of the simple translations suggest. This isn’t the fault of the translators. “Rei ni hajimari rei ni owaru.” is a wonderful little aphorism and when doing translation, you can’t stop in the middle of the work to add your own 3 or 4 page explanation of one quick phrase, so you go with what feels closest to the intention of the particular passage.

As the diagram above suggests, there is a lot more wrapped up in rei 礼 than any of the simple translations might suggest. The definition below is from the Kenkyusha Online Dictionary.

|

2 〔おじぎ〕 a salutation; a salute; a bow; an obeisance;

| |

3 〔儀式〕 a ceremony; a rite.

4 〔謝辞〕 thanks; gratitude; acknowledgment; appreciation.

When I first started my journey in the world of Japanese budo, meanings 1 and 2 above seemed the most important to me. The further I journey the less important those become, and the more emphasis falls upon the fourth item “thanks; gratitude; acknowledgment; appreciation.”

Etiquette, courtesy and bowing are all external forms. If those forms are empty and just something you do, they have no meaning. Fill that bow, that formal etiquette with sincere feeling of thanks, gratitude, respect and appreciation and it comes alive for you, and for whomever receives it. Budo is a way, and a part of that way are the forms of etiquette and courtesy.

The forms aren’t there just to look nice. They are there to teach us something. When we first start training in a way, they teach us the proper forms so we don’t look like fools and annoy other folks along the way. At this stage, folks like me have enough trouble just remembering the proper movements and when to do them. When we forget something there is always some supercilious fool who is more concerned with form than content who is thrilled to demonstrate their superiority by correcting us in the most embarrassing way possible.

As much as I feel sorry for those who have to deal with supercilious fools as they progress along their way, I pity the supercilious fools even more. They’ve missed the entire point of the practice. Etiquette and courtesy are things we should be giving to everyone, those above us and those below us. The most senior, accomplished and masterful martial artists I have encountered are also the most courteous, patient, polite, respectful and forgiving. They have learned and internalized the lessons present in the forms of etiquette and politeness that we use during practice. When they bow, it is not an empty gesture because that is what is expected from them. It is a meaningful symbol of what they think and feel.

First we learn the forms of etiquette and courtesy. Then we learn to fill these empty vessels with gratitude, respect and every other feeling that is valuable. There are many, and I doubt that I have learned them all. The first one, the most obvious, is respect. The first bows in our journey along the way are to our teachers when we are introduced to them and they welcome us as fellow travelers on their path. It’s easy to bow with respect to them. They will probably be looking for signs that our respect is sincere, and certainly a worthy teacher will bow with respect for her student. After all, the teacher understand intimately just how difficult the journey is, and respects the student who earnestly desires to travel it.

Similar respect is due to all our fellow students. They are showing up for practice, working with us and letting us work with them. And this isn’t ikebana or cha no yu, but budo! If someone is in the dojo practicing with us, they are giving us their body to use for our training, even as we return the favor and let them use our bodies for their training. This is true whether it is judo or aikido or kenjutsu or jodo or naginata. We are training together. How someone cannot respect a partner who is giving you the gift of their healthy body to train with I cannot fathom. Every time I bow to a training partner it is with respect and honor to them for the great gift they give me by training with me.

That feeling led me to the fourth meaning of 礼 rei in that definition above, thanks, gratitude and appreciation. I really do appreciate my training partners. I couldn’t go any further along the budo path without them than I could without a teacher. True budo is not an isolated practice. It only happens with other people. I respect my teachers and fellow students, but even more, I am grateful and appreciative of them. They make all my practice possible. They give me the gifts of their time and their experience and their wisdom and their bodies to train with. They don’t have to give me any of these things, but all are cheerfully and warmly given.

My gratitude is especially deep when I consider my teachers. I really can’t think of one good reason that Yoshikawa Sensei or Takada Sensei, or any of my other teachers should have been willing to put up with an an uncouth young guy who had only the barest understanding of etiquette and proper behavior, and whose Japanese was certainly not up to the task of easy, clear communication.

Takada Sensei and Kiyama Sensei in particular are wonders to me. They both fought in World War 2. They had no particular reason to love their former enemies. They have both so transcended that sort of thinking I am amazed whenever I consider it. Takada Sensei used to take great pleasure in explaining the progress of the world by showing them the sword he used for practice. It is a beautiful blade from the 1500s that has been in his family for hundreds of years. It is a huge, heavy beast of a blade made for the wars in Japan at that time. In the 1940s, as Takada Sensei was going off to war himself, he had it remounted with the saya and tsuka of a Japanese infantry officer so he could carry it. It is still mounted that way. He would point out that 60 years before he had carried that sword to war to kill Americans, but now he carried it to share his culture and art with Americans. He had grown, and so had the world. I miss him very much.

Kiyama Sensei is another amazing man of that generation. A fighter pilot during the war, he and Takada Sensei had studied iai with the same teacher in the 1950s. When Takada Sensei passed away, Kiyama Sensei graciously accepted me into his dojo so I could continue my journey. He has welcomed me and taught me and corrected me when I started down dead end paths with warmth and firmness, with courtesy and respect. I’m not special there though. I’ve often watched him at the end of kendo practice. All of the students, from those in kindergarten to those in their 50s and 60s, take a moment to kneel with him, bow and say “Doumo Arigatou Gozaimasu” or “Thank you very much”. Sensei returns every bow with focus and sincerity. He never tosses off a quick bow so he can get on to something else that might seem more important. There are always seniors and other teachers talking with him at this point. He always stops and gives every student, no matter how young or old, his full attention. When they bow, he bows just as deeply and offers them the same appreciation “Doumo Arigatou Gozaimasu.”

How can a teacher of Kiyama Sensei’s rank and status give so much attention and respect to even the smallest of children? He is no longer following the proper etiquette. Kiyama Sensei acts with the full meaning of 礼 rei. His etiquette is guided by his appreciation and gratitude and respect for each of his students.

How else can I bow when I think of Takada Sensei and Kiyama but with gratitude and appreciation and respect?. Takada Sensei is no longer with me, but I can see that through the study and practice of the violent arts of budo, he and Kiyama Sensei transcended simple etiquette. Kiyama Sensei clearly does respect all of his students. His gratitude and appreciation for them for joining him on this journey is obvious when I think about it.

This is the lesson of rei ni hajimari rei ni owarimasu. Simply following the etiquette is merely the first step. With practice we hope to learn to respect everyone. We strive to appreciate each person we meet on our journey, and to be grateful for the good they bring into our lives. Pretty deep ideas to hide in some stuffy etiquette. Everything begins and ends with rei.